How to Improve Sight-Reading Skills

How to improve sight-reading skills An Introduction to Sight-Reading What exactly is sight-reading? Sight-reading is the ability to look at a sheet music chart and sing it for the first

Here we provide the basics of music theory explained in such a way even novices can learn. First, and most importantly, music theory is the language of how we “speak” in song or with instruments. For instance, it is a descriptive language that tells us what note to use, how loud or soft we should sing, and what kind of emphasis and/or tempo we should use.

In other words, music theory helps performers express emotions. The song writer, arranger, or Director might want the listeners to feel specific emotions when the piece is performed. Therefore, words on the page simply convey an emotion. Music theory explains the way notes or combination of notes together (known as a chords) are sung in a way to evoke the meaning.

As performers of choral a cappella or four-part harmony, music theory is vital to our successful performance of any given piece. Our Director of Music, Ben May uses this device to inform us, his singers, of his interpretation of how the piece should technically be sung. This accomplishes the emotive goals of either the song writer or the arranger.

For many of our songs, Ben spends time explaining how he wants us to sing specific measures and rhythms, even what he wants us to think about while singing. Likewise, it shows us and the audience the connections between words, meaning, and feelings. We work on getting into character so we can feel the meaning behind the story. That approach helps us tell a compelling story.

We think that it is in a singer’s best interest to learn the concepts of basic music theory. Music theory concepts are especially important in the a cappella and barbershop styles of singing. Therefore, the two styles can be very technical in nature, especially when trying to achieve the sounds of specific power chords.

When using learning tracks, sheet music, and singing at our rehearsals, guests can pick up and learn to sing using music theory. Above all, if you’re just starting to sing, the best way to learn is to combine singing with learning the theory behind what you’re doing.

Continue reading to learn to sing with the basics of music theory. If you want to learn about the four vocal parts in the barbershop style of singing, please read our article The Basics of Barbershop Explained.

Singing comprises three distinct “voices” each with different levels of resonance that are used to produce specific sounds. Singers will feel the vibration of the notes in different parts of their bodies depending on which voice they’re using.

A technique used to sing notes significantly higher than one’s normal range. It has been described as “sounding like a woman or female” when singing. Falsetto is typically used by a tenor almost always and when necessary by a lead, baritone, or bass singer. Switching into falsetto is recommended for high notes because, in general, it is safer for a singer to use falsetto because it is easier on the vocal cords.

When the singer feels the tone or note resonating in their heads instead of in their chest. For example, a bass may need to switch into head voice in order to sing notes at the top of their vocal range.

Head Voice / Chest Voice Mix or mixed voice is when a singer combines chest and head voice together. This happens when we shift the voice from our lower to upper range at our “breaking” point. This is when the singer’s voice wants to shift into head voice but the singer stays in chest voice.

This voice type is used for the lowest vocal register and provides the most resonance available to a singer. It is used frequently by basses and baritones.

This occurs when a singer “crosses” between and amongst the different voices. The will be a bridge when going from chest and mixed voice and another between mixed and head voice.

As mentioned above “mix” refers to a head/chest voice mix.

A technique of opening the throat to “darken” a vowel in order to ascend a voice from low to high to be able to hit higher notes in the vocal register.

In choral and a cappella singing there are five specific vowel sounds used: Ah, Eh, Ee, Oh, and Oo. Each vowel sound has a specific way the singer needs to form the vowel sound with their lips, mouths, and jaw. The reason why we sing specific vowels is to get the resonance we need for a note to sound right. Using the right vowel shapes can also help singers with the pitch. We strive to sing in a relaxed way – with as little strain as possible on the vocal cords.

Modified vowel sounds for Ah:

Our modifications following the path Neutral/Wider/Narrowing/Narrow and have the subtle intention within the soft palate (not pronounced within the mouth) of Hard/Hawed/Heard/Who’d.

Chest Voice – Neutral raised soft palate

Chest Mix – Wider raised soft palate

Head Mix – Narrowing soft palate

Head Voice – Fully narrow raised soft palate

Modified vowel sounds for Ay:

Chest Voice – Hey; usually breaks around E4

Chest Mix – Head;

Head Mix – Hid; usually breaks around G4

Head Voice – Heed

This is where you place the vowel sound in your throat when you sing. Placement is where you place the sound of your vowels in the front of the mouth or the back of the throat. Resonance and tone for each note will be impacted depending where the note is sung.

The consonant sounds are our enemy! They do not resonate nearly as well as vowel sounds. In some cases, we leave off the consonants completely. Choruses can almost always guarantee that someone will sing the consonant which means not everyone needs to sing it.

Our chorus has been working on exposing our top teeth when we sing certain vowel shapes like Ah. When we do, we create more resonance and a better tonal quality. In other words, we can create a brighter sound.

We must see that music theory is not only about music, but about how people process it. To understand any art, we must look below its surface into the psychological details of its creation and absorption.

Marvin Minsky

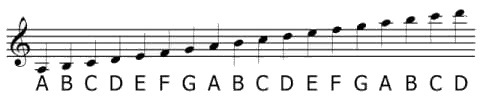

There are five horizontal lines upon which these notes are placed, known as either a staff or stave.

Written music is broken up into multiple small sections for easy reference called measures. Each measure is numbered from the beginning of the music to the end. Regardless of if you sing using the treble or bass clef, each singing part will be performing their part of the music in the same measure at the same time. Notes in the measures are placed either on the stave, above, or below them.

There are a total of seven notes used in all basic music theory: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G each with its own unique sound, known as pitch. Notes can also be played a half step up or a half step down as either a sharp or flat. Many people use mnemonic devices to try to remember these notes. The tricks people use are very much dependent on which clef is being used.

The flat symbol means to sing the note in a lower pitch by one half step than written on the sheet music.

A double flat means to sing the note in a lower pitch by one full step than written on the sheet music.

This means to sing the note in the original and unaltered pitch – ignoring any flat or sharp symbols or if the key denotes that the note would be sung flat or sharp.

Like the flat symbol the sharp symbol denotes a change in pitch. Unlike the flat symbol which tells a singer to sing lower by one half step, the sharp symbol tells the singer to sing one half step higher than written.

Similar to the double flat symbol, the double sharp symbol denotes a full step change in pitch.

Each stave in basic music theory also has what is called a “clef” at the beginning of each line. This symbol communicates to the performer what pitches or notes should be sung or played.

A bass clef is also known as the “F” clef because it locates F on the staff. You can then locate any note either up or down the scale. The bass and baritone parts use the bass clef.

The treble clef is also known as the “G” clef because it locates the G note on the staff. Like the F clef, it helps the lead and tenor parts orient on the right notes to sing either up or down the scale.

Common ways to remember the proper order of the notes on each stave include the following mnemonics.

Treble Clef:

Notes on the lines: (E)very (G)ood (B)oy (D)oes (f)ine

And then the notes in the spaces: F A C E

Bass Clef:

Notes on the lines: (G)ood (B)oys (D)o (F)ine (A)lways

With the notes in the spaces: (A)ll (C)ows (E)at (G)rass

Many people learn the proper note sequences by regularly playing or practicing scales. That is when you play or sing the notes in ascending or descending order while mentally thinking about where the note is placed on the clef. In singing, that technique is known as Solfege.

Scales are notes in either half-steps or whole-steps that are ascending or descending that spans an octave. A scale can have anywhere from 5, 6, 7, 8 or more notes in them. Major scales have only 7 notes. Every type of scale can have 12 possible starting notes which may include flat notes and sharp notes.

We discuss different chords in The Basics of Barbershoping Explained.

The solfege system is a technique used much in the same manner of scales. Words are used to represent the same notes in a scale: Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti-Do. It is used primarily to teach singers how to hear and visualize notes, pitch, and is useful in sight reading sheet music. Solfege is used to help singers match reference notes and is a skill particularly associated with relative pitch.

Perfect pitch is when a singer can either sing or identify a note without using a reference pitch. If someone is singing, it means that they can sing the note perfectly in tune on their first try.

Relative pitch is a skill that singers use to “find their note” based on a reference note. Singing in close harmony requires singers to adjust their pitch in order to create harmonic effects. We discuss this necessity in Relative Pitch. Read more about these concepts in our article Relative Pitch Part Two: Relative vs Perfect Pitch.

The most commonly employed tuning technique is to use relative pitch. By using a pitch pipe or TE Tuner, the reference note (usually the key) is played. The singer(s) then find their starting notes using the reference note.

A set of musical techniques to change the rhythm of a piece of music. This occurs by stressing a different note that throws the beat off or by stressing an off-beat. The accented note can or stress can be placed in wide range of rhythms and notes. For example, an accent on a particular note, slightly before or after a beat. Syncopation has been employed since, if not before the Middle Ages.

Time signatures give a song its beat. The top number provides the number of beats in each measure while the bottom number provides the value of those beats. If the bottom number is 4, that means the notes have a value of quarter notes. The value of 2 means half beats and an 8 means eighth beats. A time signature of 4/4 means there are 4 quarter beats in each measure.

Any time signature where the top number in the beat is either a 2, 3, or 4.

All notes have specific values depending on the time signature in question. Assuming a time signature of 4/4, if you only had one type of note, they’d have specific values designated by the time signature. Notes are arranged in a specific way as to express the emotions that they want the singer to use in order to convey feeling or a message to the audience.

In 4/4, a whole note would be held for 4 beats.

With a 4/4 time signature, there could be 2 half notes and they’d each have 2 beats.

Again, using 4/4 there could be 4 quarter notes and each has 1 beat.

In a 4/4 time signature there could be 8 eighth notes and each has 1/2 a beat.

Using 4/4, there could be 16 sixteenth notes and each has 1/4 of a beat.

A singer is asked to hold a note an extra beat when there is a dot notated next to the note.

Rests work similar to notes with notable exception that when you see a rest, they are not played or sung. In a similar way to notes, rests are also used selectively to express the feelings of the author, composer, or arranger.

In a 4/4 time signature, a whole rest is held for 4 beats.

Using the 4/4 time signature, there are 2 half rest and each has 2 beats.

There are 4 and each has 1 beat in a 4/4 time signature.

In a 4/4 time signature, there are 8 eighth rests and each has 1/2 a beat.

There would be 16 sixteenth rests and each has 1/4 of a beat in 4/4 time signature.

A singer is holds a rest an extra beat when there is a dot notated next to the rest. Dotted rests are typically not used in musical pieces using simple time.

Dynamic markings are printed notations on sheet music that tell performers how loud or soft to play or sing the music. They can be words, abbreviations, or symbols. Expression markings describe other modifications to the written music. For example, tempo changes, different time signatures, or a marking to emphasize or de-emphasize a note or measure.

This symbol means that the singer takes a breath at the designated spot in the sheet music. Usually this means that singing through the next part or measures are important that the singer does not breathe.

Crescendos and decrescendos are known as expressions.

A crescendo is when the singer(s) or notes gradually get louder. It is not intended to be a loud or immediately percussive sound.

The decrescendo is the opposite of a crescendo. This is when a singer gradually gets softer in volume over a measure or multiple passage.

A fermata is a mark over a note telling the singer to hold the note for an unspecified amount of time. It looks like an eyebrow over a period. The amount of time a singer holds the note is determined by the Director conducting the piece but is sometimes double the note value. A fermata can also be placed below a note upside down and it means the same thing – hold the note.

How to improve sight-reading skills An Introduction to Sight-Reading What exactly is sight-reading? Sight-reading is the ability to look at a sheet music chart and sing it for the first

Generally in most years, the SWD sponsors an annual Chorus and Quartet competition. The exception is the pandemic year we experienced due to Covid-19. There was no competition during the pandemic. The BHS recent resumed chorus competitions in 2022.

The Tidelanders excitedly sponsored our first singing competition. We promoted the contest to over 200 high schools in Harris and Fort Bend counties in Texas. We announced two winners (Men’s and Women’s) mid-April. We are looking forward to planning a bigger contest next year.

The Houston Tidelanders Chorus is pleased that we were able to perform for Clear Lake audiences once again! We’ve been performing in the Clear Lake area for about 25 years and it’s one of favorite shows.

“Smile” continues to be considered timeless. Meaning the message always seems to be relevant. As long as it continues to be popular, artists will continue to cover and interpret it’s meaning in order to continue to have it resonate with audiences. Modern artists like Michael Jackson have arranged and performed it.